Introduction

“The carved wood furnishings of so many Timurid buildings deserve a study in themselves, which has never been undertaken“.

This sentence published in the groundbreaking work on Timurid Architecture by L. Golombek and D. Wilber (Golombek/ Wilber 1988, p. 136) was the trigger for a research project that began in 1994.

The project aimed to analyze and interpret a substantial collection of a specific type of material culture which has been produced in Iran and Central Asia mainly during the Timurid period (c. 1370 to c. 1510). While only few examples from a secular context have survived, the bulk of material, mainly doors, grills (mashrabiyas), minbars and cenotaphs, belongs or belonged to religious buildings, mosques, madrasas and mausolea. The latter ones are often shrines of descendants of the Imams, spreading all over Iran, but with a strong focus in the northern provinces of Mazandaran and Gilan, which are rich on trees and therefor on wood, too. Many objects contain inscriptions at various length providing beyond religious texts (Qur’an, Hadith among others) historical information as the name of the patron, the name(s) of the wood worker(s) (najjār) and the date when the object has been produced allowing to prepare a framework of dated woodwork during the 14th to 16th centuries. Beyond its historical and art historical approach, this project also has a heritage related aspect: the “virtual protection” of material which has been and still is under permanent threat to be neglected, over-restored or stolen.

For some aspects see the articles by Joachim Gierlichs, Tabrizi Woodcarvings in Timurid Iran and Imamzadagan in Iran: Überlegungen zur Entwicklung und Ausstattung

Woodwork of the Timurid Period has not been a research topic on its own until very recently, inspite of the fact that first attempts to collect the material were already made during the second half of the 19th (B. Dorn) and the early 20th century (L.H. Rabino), continued by L.A. Mayer (collection of wood workers in the Islamic World), R. Hillenbrand (cat. entries on Mazandaran in Golombek/ Wilber) and others.

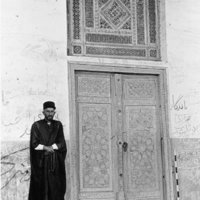

Due to the imense changes in Iran and Central Asia during the last decades historical photo material becomes more and more important. One of the few scholars who paid attention and provided a detailed photographic documentation of Persian/ Iranian woodwork is Myron Bement Smith (1897-1970). Unfortunately he didn't publish much, but his estate is kept in the archives of the Freer and Sackler's Galleries (now National Museum of Asian Art), Smithonian Institution in Washington, D.C.. An example can be seen the below.

During the academic year 2018-2019 at the Alexander von Humboldt Kolleg for Islamicate Intellectual History at Bonn University (chair: Prof. Judith Pfeiffer) the idea has been developed to present the core of the collected material in an on-line database hosted by the Bonn University and State Library, whose digital services department customized the OMEKA database software reflecting the existing data sets.

The selection of more than 200 pieces of woodwork was determined by several factors: availability of data, artistic and historical significance and photographic documentation. The majority of the material has been collected and photographed in 1995 und 1996 during several surveys in Iran and Central Asia. More than 20 sites (buildings) were revisited on a short trip to Mazandaran, Iran in 2019 with support of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Presenting this website and sharing the information stored in the database behind it with researchers and scholars, it is hoped that research into Islamic woodwork will be advanced. For any exchange of information related to the content of the project (questions, suggestions, etc.) use contact.

Credits:

This project has been supported over the years by many institutions and individuals, the main institutions are listed below (more information on the history of the project is under preparation)

- Gerda Henkel Stiftung / Gerda Henkel Foundation

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft / German Research Foundation

- Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Aussenstelle Teheran (Eurasien-Abteilung) / German Archaeological Institute, Tehran Branch (Eurasia Department)

- Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Turkologie/ Institute of Turkic Studies

- Alexander-von-Humboldt Kolleg, Universität Bonn / University of Bonn

- Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Bonn / Bonn University and State Library

-

Cenotaph of 1353-1354 (?) from Iran, Mazandaran

Der Kenotaph (Casket B = Bivar, pl. 70) ist photographisch nur unzureichend dokumentiert, lediglich eine Längsseite ist abgebildet. Sie ist horizontal zweigeteilt und mit einem geometrischen Dekor gefüllt, der auf 8-strahligen Sternen, eingefasst von Hexagonen, basiert. -

Cenotaph (Post) of 1400-1499 from Iran, Mazandaran

Der Kenotaphpfosten gehört zum Kenotaph für Tahir wa Mutahhir im Imamzadeh Tahir wa Mutahhir. -

Door of 1400-1499 ? from Iran, Mazandaran

Die doppelflügelige Tür weist die typische Dreiteilung auf: ein großes langrechteckige Mittelfeld ist von je einem deutlich kleineren querrechteckigen Feld oben und unten eingefaßt. -

Tympanum of 1358-1375 ? from Iran, Isfahan

Das Tympanon ist mit einer mehrzeiligen Inschrift (Koranvers) versehen, die das Innenfeld und den Rand bedeckt (Siroux 1954, 16, Anm.1). Es existiert kein publiziertes Photo dieses Tympanons, weshalb weitergehende Angaben nicht gemacht werden können. -

Cenotaph (Panel) of 1400-1499 from Iran, Mazandaran/ Gilan

Es handelt sich um eine Kenotaph-Längswand (Langseite) mit den beiden Aussparungen für die beiden Quer, bzw. Schmalseiten. Der geometrische Dekor basiert großen Hexagonen, die ihrerseits mit sechs (6) Drachen gefüllt sind. .... Beide horizontale Balken (oben und unten) tragen Inschriften, ebenso wie die Vertikal verlaufenden Rahmenteile. -

Leaf of a Door of 1424 (?) from Central Asia, Uzbekistan

Der rechte, aus einem massiven Brett gefertigte Türflügel ist mit Ausnahme der abgesägten Türzapfen vollständig erhalten. -

Door of 1405 from Central Asia, Uzbekistan

Die schmalen, hohen Türflügel sind durch ein großes Mittelfeld, das von zwei kleineren, quadratischen Paneelen oben und unten gerahmt wird, gegliedert. Rahmen und Querverstrebungen sind mit einem geometrischen Ornament versehen, das aus unterschiedlichen Hexagonen besteht, die z.T. Schnitzdekor, aber auch Einlagen aufweisen. Die oben beschriebene Gliederung ist typisch und konstruktiv bedingt bei einer Rahmenfüllungskonstruktion, die hier jedoch nicht vorliegt. Es handelt sich vielmehr um eine reine Brettkonstruktion, bei der z.T. auch die "kunde kari-Technik" imitiert wird. Das große Mittelfeld weist ein Medaillon auf, während das untere Paneel mit einem Dekor aus Sternen und Kreuzen (untypisch für Holzarbeiten der Timuridenzeit) geschmückt ist. -

Tympanum of 1358-1375 from Iran, Isfahan

Das Tympanon besteht aus einem spitzbogigen inneren Feld und einem relativ schmalen äußeren Rahmen. Sein Dekor unterscheidet sich deutlich von den (etwas späteren) timuridischen Beispielen, da hier das innere Feld nicht mit mehreren waagerecht verlaufenden Inschriftzeilen gefüllt ist, sondern einen floralen Dekor aufweist, in den mittig zentriert eine große kalligraphische Inschrift gesetzt wurde (kreisförmig verlaufend?). Der Dekor ist in dieser Anordnung unik. -

Tympanum (Grille) of 1470-1500 from Iran, Mazandaran

Das durchbrochen gearbeitete spitzbogige Gitter ist höchst wahrscheinlich zeitgleich (ca. 1470-1500) mit der zugehörigen, inschriftlich datierten Tür entstanden, über der es sich befindet. Seine äußere Form entspricht den massiven Tympana, die zumeist mehrzeilige Inschriften aufweisen (vgl. z.B. Berlin, Museum für Islamische Kunst). Es diente der Licht und Luftzufuhr in dem engen Grabbau. Eine in den 1930er Jahren gemachte Aufnahme (MBS) belegt, daß es sich nicht um eine moderne Arbeit handelt. -

Door of 1404-1405 from Central Asia, Uzbekistan

Die aus einem Brett (?) gearbeiteten Türflügel sind in drei Felder unterteilt, ein großes Mittelfeld wird von je einem annähernd quadratischen (oben) bzw. rechteckigen (unten) Feld eingefaßt. Das Mittelfeld ist mit einem filigranen vegetabilen Dekor geschmückt, der heute aufgrund der Übermalung kaum zu erkennen ist. An wenigen Stellen im Randbereich der Türflügel, wo die Übermalung abgenommen wurde bzw. abgefallen ist, kommt die originale "Struktur" der Tür zutage. Sichtbar wird z.B. eine Art "Fischgrätdekor" mit Knochen- oder Elfenbeineinlagen. Die oberen Felder tragen kurze Inschriften, während die unteren Felder einen Floraldekor aufweisen. Vollständig erhalten hat sich der Mittelbalken, der im oberen Drittel am Übergang vom runden Mittelteil zum rechteckigen oberen Abschluß die Meistersignatur aufweist.